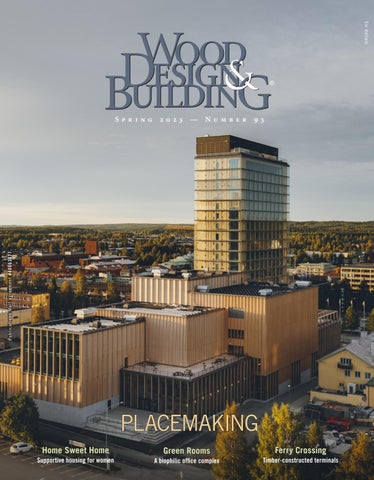

Bringing nature inside—through biophilic design—provides health, cost, and environmental benefits.

Joel Kranc

As the waves of COVID-19 ebb and flow with the seasons, and the general population is trying its best to move on with some sense of normalcy, a few concerns remain in focus. First, mental health issues—resulting from the uncertainty of the pandemic and extended isolation—persist and will likely be felt for years to come. Second, indoor spaces and cramped gatherings are not as welcome as they used to be.

Re-engaging with nature has, in many ways, addressed both of those issues. People are looking to relieve their stress in any number of ways now more than ever. They’re also looking for outdoor spaces to enjoy. Note the rise in pool construction. According to IMARC Group, the size of the global swimming pool construction market hit US$6.7 billion in 2021, and is expected to reach US$8.4 billion by 2027.

How does a reconnection with nature manifest itself into our environment going forward? Design and architecture professionals are taking note of these new needs/concerns and are incorporating more natural elements into their projects. Biophilic design is a concept used within the building industry to increase occupant connection with the natural environment through the use of direct nature, indirect nature, and space and place conditions. Used at both the building and city scale, biophilic design, experts argue, has health, environmental, and economic benefits for both building occupants and urban environments.

Practically speaking, wood in the biophilic design environment provides easier-to-construct, high-quality facilities that minimize carbon footprints. The energy required to provide a wood building is less than steel; carbon is taken out of the atmosphere, and wood is renewable and sustainable.

David Fell is a B.C. researcher who has studied the positive impacts of incorporating wood into the design of buildings and co-author of a report on how wood can be a restorative material in healthcare environments.

For example, the report, quoting other studies, indicates the following:

– Adding cedar wood panels and rice straw paper to the walls of a hospital isolation room reduced stress levels (measured by cortisol levels) experienced by people in the space compared to people who spent time in the room when it had its original concrete walls (Ohta, et. al, 2008).

– When plants and natural materials (e.g., wood, cane) for furniture are used in communal spaces in care homes, the subjective well-being of people living in those homes is enhanced compared to situations where these are absent (Weenig & Staats, 2010).

– Assisted living facilities are seen as homier—by patients and their families—when more natural materials, such as wood (as in siding), are used on the outside of their structures (Marsden, 1999).

One area where wood and mass timber are making a noticeable difference in the health of individuals is within the aging population and assisted living facilities. Case in point is the Gateway Lodge Long-term Care facility in Prince George, B.C.

Gateway Lodge Long-term Care provides 94 complex care beds using a decentralized approach that places small groupings of 14 to 20 residents into linear “home areas.” The residential rooms are located along the perimeter of each home area and have views to the site’s many gardens and courtyards. The double exposure of each home area ensures abundant access to natural light, views, and fresh air.

The architects used a shorter than usual construction timeframe to implement a 2 x 6 dimensional lumber and Douglas fir plywood prefabricated wall panel system, which allowed the construction team to frame the entire 13,750-sq.m facility in only 12 weeks. As foundation work progressed, the panels were manufactured off-site and delivered as the foundation of each “home area” was completed.

Another facility featuring wood in its biophilic design is the Minoru Centre for Active Living in Richmond, B.C. The decision to use wood over other available construction materials was due to the City of Richmond’s high water table, and geotechnical concerns such as soil instability and buoyancy, which would put a considerable amount of pressure on the underground pool tanks. Because wood is significantly lighter than steel or concrete, the structural load of the roof was reduced, minimizing the facility’s foundation requirements.

“The City of Richmond’s goal was to develop an iconic facility, so wood became a material of choice for the undulating roof. Wood has a highly aesthetic appeal, while delivering required durability, acoustic, and structural characteristics for the project,” according to Jim Young, director, Facilities and Project Development, with the City of Richmond.

Good Timing

The timing of the growth of biophilic design in Canada is not a coincidence. There are changes emerging that have made the design more attractive and easier to apply. According to Graham Lowe’s report Wood, Well-being and Performance: The Human and Organizational Benefits of Wood Buildings, there are changes emerging that have made biophilic design more attractive and easier to apply. These changes include the following:

– Building code updates that permit larger and taller wood buildings, including the 2020 National Building Code of Canada provisions that now permit encapsulated mass timber construction in buildings up to 12 stories;

– A move towards climate change action and the adoption of more sustainable construction and building renovation practices;

– Employers’ focus on improving employee well-being that allows for opportunities to change the physical workspace; and

– Corporate sustainability strategies that are more closely linking environmental and human resources department goals. It would seem that the intersection of sustainable design and biophilic design is driving design decisions that will help improve lives.

“We’ve just secured the green roofs on a $1-billion hospital project in Vancouver called St. Paul’s,” notes Ronald Schwenger, principal and founder of Architek. “It wasn’t that long ago that when they looked at a hospital, they didn’t consider green roofs or any natural element on them because they felt hospitals needed to be sterile. And it’s now exactly the opposite. They know that patients’ well-being is greatly improved when they’re around natural light and biophilic elements,” he adds.

Schwenger says he’s 100% convinced that our direct connection with nature has a profound effect on well-being, mentally and physically. Most of the projects he works on are in the residential space, made of wood frames. “There is a myth floating around that green roofs or biophilic elements like living walls don’t work well on wood-frame buildings. But if they’re engineered and done correctly, they actually protect the building.”

Road to Well-being

Research done by the Canada Green Building Council in its report Healthier Buildings in Canada 2016: Transforming Building Design and Construction suggests that “the prognosis is good for increased investment for health and well-being as an integral part of green building design and construction in the years to come.” This goes for wood-based biophilic designs.

In addition, happy employees help with the bottom line. Working in a green building can improve an employee’s job performance. Studies show that office workers in green-certified buildings, compared to those in conventional buildings, have better cognitive functioning (decision-making), mainly due to better-quality indoor environments.

In his report, Fell adds that “the psycho-physiological reactions of human beings to wood are based on two major systems of reaction to stress; namely, the autonomic nervous system and the endocrine system. One particular research project on the response of the autonomic nervous system to wood observed lower levels of blood pressure and heart rate in an environment where wood is present, compared with one where it is absent.”

The Wood Products Council, quoting the report Economics of Biophilia, takes a bottom-line approach as well. Retention of employees is an investment worth taking. Termination, the report suggests, costs $1,000; replacements cost $9,000; and lost productivity costs $15,875. The total cost for the employer losing one employee is $25,875. The connection to visible wood and other natural elements allows employees to remain connected, have enhanced concentration, improve their overall mood, and lower stress. Therefore, biophilic design is not simply good design, it also makes good business sense.

Despite the ever present and continued construction of glass and steel towers around the world, biophilic design—and its incorporation of wood and mass timber—is being proven as healthier, more aesthetic, and, over time, a more cost-efficient alternative. Wood form and function are turning new biophilic-designed structures inside out.

Joel Kranc is an experienced and award-winning editor, writer, and communications professional. Currently, he serves as director of KRANC COMMUNICATIONS, a full-scale marketing and content firm founded in 2011 serving a global financial services clientele.